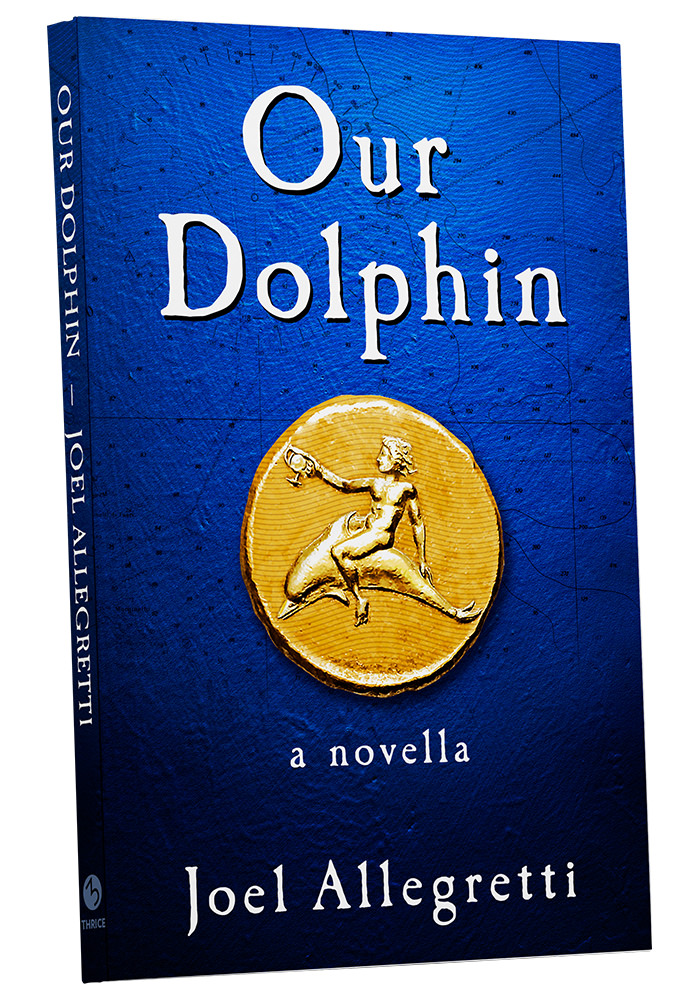

THRICE PUBLISHING™ NFP is proud to announce the publication of the first book in our library of independent titles, Our Dolphin by Thrice Fiction contributor Joel Allegretti. Our Editor at Large, RW Spryszak, chatted with Joel as we were working on his book.

RW SPRYSZAK: Can you describe the evolution of the idea behind Our Dolphin?

JOEL ALLEGRETTI: Our Dolphin is a tribute to a few of my literary obsessions.

Although the novella takes place in an unnamed Italian village and Tangier, the plot stems from my interest in Latin American magic realism, which has had a significant influence on me, particularly the works of Gabriel García Marquez and Jorge Luis Borges (I don't know Spanish, so I have to read translations). In the case of Our Dolphin, the influence is more García Marquez than Borges.

The protagonist, Emilio Canto, is born with a strange birth defect, which I invented. The inspiration for Emilio was my favorite literary character: Erik, better known as the Phantom of the Opera. All Emilio and Erik have in common, however, is a disfigured face. Their personalities are nothing alike. Emilio is the innocent only child of an Italian fisherman and his wife, whereas "innocent" isn't an adjective we can assign to the Phantom of the Opera.

The influences on the scenes in Tangier were Paul Bowles and William S. Burroughs, who's my favorite Beat writer. In fact, Moore, a principal character in the Tangier section, is based on Burroughs. I spent a week in Andalusia in 1990 and took a day trip to Tangier, which helped me visualize the medina (the old city) as I wrote. I have to emphasize the Tangier of Our Dolphin is a Tangier of my imagination.

I give a little nod to Fellini in Our Dolphin. Emilio's cousin is named Federico. His mother is named for Giulietta Masina, Fellini's wife and the star of several of his films. I thought of calling Emilio's father Federico, but decided it would be a bit much, so I named him Leonardo, but not for da Vinci, or DiCaprio.

RWS: Your work has spanned the disciplines of poetry, fiction and theater. How do you decide which form an idea is best suited for? There are many evocative passages in Our Dolphin that seem to echo poetry, though the work is in a fictive form. What determines the venue for an idea?

JA: As ironic as it may seem, the poetic passages in Our Dolphin were influenced by prose, not poetry. As I noted above, Latin American magic realism was an inspiration. Gabriel García Marquez, the master magic realist, can be florid and otherworldly. I think the passages in Our Dolphin you refer to, as well as phrases like "a gull of mythological proportions" and "the face that brought her infinite despair," are evidence of the influence.

Most of my other fiction doesn't try to be so poetic. For example, I wrote a short story called "The Very Special Birthday Dinner," about a widow who is preparing a 30th-birthday celebration for her son, a veteran of the Iraq War. I use straightforward language to tell a story about everyday people.

As far as theater is concerned, I'm pure dabbler. I've written only a few theater pieces, and two of them are poems arranged as performance texts. Another is a five-minute Dada-inspired play that I wrote as a lark; it's about a romantic dinner between a young businessman and a rock. There are three others, one of which I technically didn't write; it's a tribute to Leonard Cohen that I was asked to stage at a New York cabaret in 2009.

RWS: Where did your first published piece appear?

JA: My first published work was a first-person account in the SoHo Weekly News, a New York paper that launched in 1973 and ceased publication in 1982. I was a journalism student at New York University. My class assignment was to interview people about the coming hike in the fare to ride the subway. With pen and pad in hand, I talked to commuters until a cop stopped me and said I was violating a city law against harassing people. He cited the local-law number. I didn’t let it rest. I found another cop and told him what his fellow officer said. He replied there was no such law with that number and made a nasty comment about the other policeman. I wrote an article about my experience and submitted it to the SoHo Weekly News, which published it under the headline “Who’s Harassing Whom?”

RWS: Did you have a notion of doing investigative journalism when you were starting out? How did a journalism class at NYU turn into poetry and all else?

JA:My writing ambitions long preceded my decision to pursue a journalism degree. I wrote little stories when I was in grammar school. I used to read them in front of the class. I was big on Jules Verne back then.

Investigative reporting never interested me. I felt more at home writing feature articles. I published a full-page feature article in The Daily News the summer I graduated college. I wrote it for a senior feature-writing class, and part of the assignment was to try placing it with a magazine or newspaper.

I was a newspaper reporter for three years after graduation. I worked for a Central New Jersey weekly, covering local government. I decided to leave journalism for public relations, because I wanted to work in New York and knew the chance of landing a job at The New York Times was next to none. My last job was director of media relations for a national not-for-profit organization. I prepared the CEO, his senior executives, and other spokespeople for press interviews.

I stopped writing for the page in my 20s. I pursued music instead. I’ve played the acoustic guitar for most of my life and wrote songs and performed. I returned to literary writing in my early 30s, when I decided to write a novel set at the Jersey Shore. Although I received some nice feedback on the manuscript, there were no takers.

I didn’t choose poetry. Poetry chose me. I belonged to a poetry group when I was in college, but didn’t resume writing poems until the fall of 1996. In February 1997 I fell in with a group of poets. I started attending readings and writing more poetry. I noticed people responded well to my poems and asked me to take part in events. Two years later, Brett Rutherford, who runs The Poet’s Press and published writers who were known on the New York circuit in the 1980s, asked me if I’d thought about doing a book. I asked, “Why? Do you want to see a manuscript?” He said yes. I spent time preparing a collection and submitted it. A couple of weeks later, I saw Brett and asked him if he’d read the manuscript. He said he’d started it. I asked what he thought. He said, “I love it.” The Poet’s Press published my first collection, The Plague Psalms, in 2000. I then had a book to promote. I thought, I guess this is what I’m supposed to be doing.

RWS: What do you do, in the meantime, to keep a roof over your head?

JA: I took early retirement, which was my plan for a long time.

RWS: That’s a dream for a lot of people. But folks I know who are in retirement often tell me they’ve never been busier. Also, I’ve heard a few writers say that they need to everyday hustle to feed their invention. What’s your take on these things?

JA: I was younger than a lot of other people who choose to retire early. In fact, when word got around that I was taking early retirement, a fellow director at the job told me other people were saying, “Isn’t he a little young?”

I didn’t intend to sit around and watch movies all day. I decided to spend my time on my literary pursuits. In other words, I was going to continue working, but in a different field. In the six years since I left the workforce, I published two collections of my poetry. I’ve published poems and short stories in journals and anthologies. I edited Rabbit Ears, the first anthology of poetry about television. NYQ Books published it in December 2015. I’ve been spending a lot of time promoting Rabbit Ears. I created a Twitter account and two Facebook pages, one for contributors and one for everybody else. I created a Rabbit Ears TV channel on YouTube, which features recordings of contributors reading their Rabbit Ears poems. I arranged readings in several states for 2016, and I managed and hosted all but one of them. I wrote press releases and sent them to the media that operated in the area where a given reading took place, which meant I was still involved in my old line of work. Having spent my career in media relations, I feel right at home taking care of the promotional end of things.

RWS: In Our Dolphin, we are specifically addressing the form and function of the novella. The main character gets all the concentration, there is a limited scope in the narrative by design. So people like to dig at it and look for subtexts. One of the most famous novellas of all time is Hemingway’s Old Man And The Sea. And when people asked him what it was a metaphor for he replied that it’s just a story about an old man and a fish. So how would you respond if some earnest, bright-eyed fellow asked you what this story is a metaphor of?

JA: I’m with Ernie on this one. There’s no intentional metaphor in Our Dolphin. It’s the story of a deformed boy and a talking dolphin. As I noted above, Our Dolphin is a tribute to a few of my literary interests.

RWS: So what’s in the works for you now? Any new projects coming down the line?

JA: I’m enthusiastic about Our Dolphin, because its publication represents my debut as a novelist, or novella-ist. My other project is my next full-length collection, which NYQ Books will publish. It’s called Platypus. It’s a hybrid work, consisting of poems, prose, and performance texts, so I named it for a hybrid animal. With Rabbit Ears, Our Dolphin, and Platypus I seem to have a mammal fixation. Maybe for variety’s sake I’ll write a book called Gila Monster.

Our Dolphin is available now from Amazon and the CreateSpace eStore.

©2011-2020 by Thrice Publishing™

All content is ©2011-2017 by their respective creators and reproduced with permission.

No part of this site may be reproduced without permission from the copyright holders.